As a pioneer in humanoid robots globally, Japan once took the lead in exploring this field but ultimately chose a full withdrawal. In 2000, Honda launched ASIMO, the world’s first interactive humanoid robot, which could not only perform complex movements but also played football with Obama on the same stage, becoming an industry benchmark. In 2012, SoftBank acquired French company Aldebaran Robotics and launched Pepper, a robot with human emotional interaction capabilities that could engage in conversations and provide information, once holding great expectations.

However, both star products failed to escape the fate of “development – mass production – discontinuation.” ASIMO had an exorbitant price tag of 2.5 million US dollars per unit; despite its advanced technology, there were no buyers. Priced at 198,000 yen and launched globally, Pepper’s total output ultimately reached only 27,000 units. During the expansion of its robotics business, SoftBank incurred hundreds of millions of US dollars in losses and debt pressure in its consolidated financial statements. After acquiring Boston Dynamics, it sold the controlling stake to Hyundai Motor Group three years later at an estimated valuation of 1 billion US dollars, presumably suffering another huge loss.

Multiple factors led to Japan’s inability to sustain itself in the humanoid robot track. Technically, the development of AI and large language models lagged behind, lacking the core foundation to support the autonomous decision-making of humanoid robots, while Chinese and American enterprises are benefiting from mature AI ecosystems and chip supply chains. In terms of industrial foundation, Japan’s electric vehicle industry is almost non-existent, making it impossible to transfer homologous technologies such as autonomous driving and multi-sensor fusion. In contrast, China and the US have laid a solid hardware foundation for building “humanoids” with their accumulated experience in the electric vehicle industry, including motors and electronic controls. On the talent and demand front, Japan has long faced a shortage of engineers and AI algorithm talents. Insufficient demand for industrial upgrading locally makes it difficult to drive the iteration of robot technology, coupled with the high price of upstream components, resulting in a lack of cost competitiveness. Today, Japan has shifted to developing “dispatch robots” relying on rules and small models, as well as hydrogen-powered quadruped robots, completely steering clear of the main battlefield of humanoid robots.

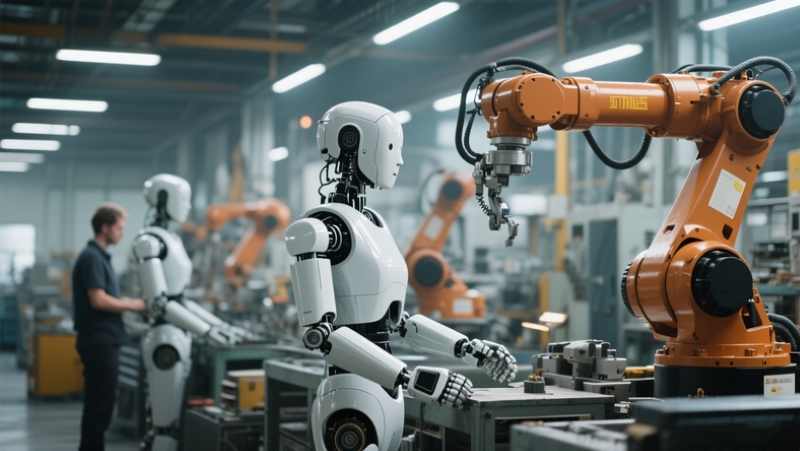

Industrial Robotics: Building an Unassailable Advantage Across the Entire Industry Chain

After abandoning the humanoid robot track, Japan focused its efforts on industrial robotics, establishing a leading position that is hard to shake. According to market data, industrial robots accounted for 71.4% of the global robot market’s revenue share in 2024. Among the world’s top 10 industrial robot manufacturers, Japan holds 6 seats, including FANUC, Yaskawa, Kawasaki, and Epson, with a combined market share of 44%. In October 2025, SoftBank acquired Swiss ABB’s robotics business for 5.375 billion US dollars, further integrating global industrial robot resources in an attempt to make up for the losses in humanoid robots in this field.

The core competitiveness of Japan’s industrial robots stems from three key pillars. Firstly, extreme stability: products can maintain continuous supply and maintenance for 20 years with unchanged models. Cooperative relationships such as FANUC with Toyota and Yaskawa with General Motors have lasted for decades. Secondly, full industrial chain autonomy: except for AI chips and a small number of high-performance GPUs, core components such as SMC pneumatic parts, THK guides, and Nabtesco reducers are all made in Japan, forming a virtuous cycle where “downstream complete machine manufacturers prioritize purchasing local upstream components.” Thirdly, engineering AI empowerment: through “Japanese-style factory AI” technologies such as machine vision, force control compensation, predictive maintenance, and automatic parameter optimization, the repeat accuracy and reliability of industrial robots have been pushed to new heights. FANUC’s ZDT series and Yaskawa’s Motoman series have already mass-produced and implemented these technologies.

US-Japan Differentiation: Competing for the Future in Different Tracks

The United States and Japan have formed differentiated layouts in the robotics industry. The United States focuses on algorithm and system innovation, defining the intelligent paradigm in humanoid, special-purpose, and medical robots and leading the latest robotic trend with technology export as the main driver. Japan adheres to the industrial robot track, leveraging advantages in reliability, long service life, and high engineering completion to maintain a leading position in the global export echelon for a long time.

For Japan, abandoning humanoid robots is not a mere strategic retreat but the result of the combined effects of economic structure, industrial paths, and risk appetite. However, the future challenge lies in whether Japan’s industrial system, built around engineering rationality, can transform when global market demand shifts from “stable repetition” to “high uncertainty” and when flexible adaptation and autonomous decision-making become core capabilities of robots. This will determine its long-term position in the global robotics industry.