In late July 2025, the Bernat Klein Studio, a landmark modernist building located in the Scottish Borders region of the UK, was put up for auction due to years of neglect and prolonged vacancy, with a starting bid of just £18,000. The news sparked immediate concern within the UK architectural community and cultural heritage preservation circles. Multiple organizations, including the Scottish National Trust, the Historic Buildings Trust, and the Klein Family Foundation, jointly launched an emergency intervention to raise funds for the acquisition and restoration of the building, aiming to prevent this historically significant structure from being demolished or repurposed by commercial entities.

A design masterpiece with an avant-garde style, yet a troubled fate

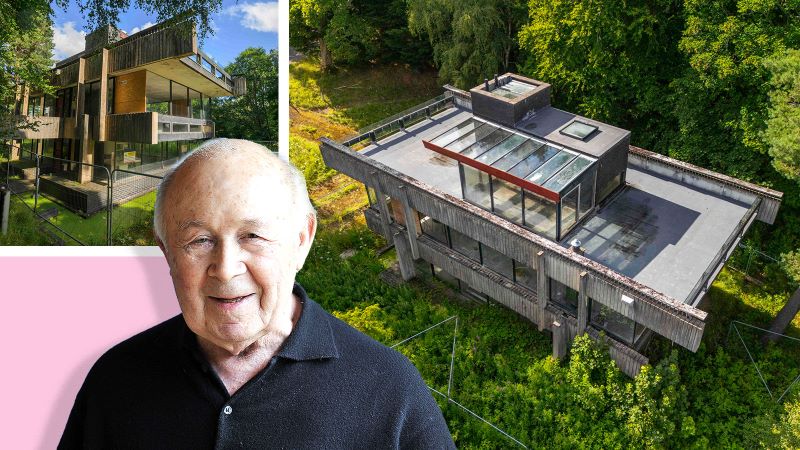

The Bernat Klein Studio was built in 1972 by British modernist architect Peter Womersley, specifically designed for renowned textile designer Bernat Klein. Located in the woodlands near Garra Hills in Scotland, the studio features a square geometric structure, full-height glass facades, and exposed concrete elements, making it a quintessential example of late modernist design. Its architectural language was directly influenced by the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier’s architectural philosophies, earning it a Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) award and designation as a Grade A listed building in Scotland.

However, following Klein’s death in 2014, the studio fell into disuse and was listed on the Scottish Endangered Buildings List due to roof leaks and structural damage. Over the years, the lack of a viable use or financial support has left this once-glorious modernist building in a state of neglect and disrepair.

Low starting bid sparks concerns, prompting urgent intervention by social organizations

In mid-July 2025, the local council officially listed the building for auction with a starting bid of just £18,000. While this figure is insignificant in the commercial real estate market, it has raised alarms in the architectural conservation community. According to an assessment by the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust, restoring and reusing the building would require at least £2.5 million to £3 million in funding. If acquired by private developers or institutions, it is highly likely to be renovated, resold, or even demolished.

To prevent this potential loss of cultural heritage, organizations such as the Bernard Klein Foundation, the Scottish National Trust, and the Scottish Architectural Conservation Association swiftly launched a joint fundraising campaign. They plan to participate in the bidding process to acquire the studio’s ownership for public use, aiming to restore it into a multifunctional public cultural space integrating exhibitions, education, and design exchanges. The initiative has already attracted a large number of supporters who have signed petitions, with architecture students and design enthusiasts voluntarily visiting the site to photograph and document it, urging public attention.

The widespread challenges facing the preservation of modernist architecture

This incident also highlights the widespread challenges currently facing the preservation of modernist architecture in the UK and across Europe. Compared to medieval churches or Victorian mansions, modern buildings are often overlooked due to their relatively short lifespan, radical designs, and high maintenance costs. Many landmark buildings from the mid-to-late 20th century have gradually lost their rightful historical status due to a lack of societal consensus and sustained investment.

Architectural critic Will Hall wrote in his column in Architectural Review: “Buildings like the Klein Studio are both a testament to design experimentation and a carrier of an era’s exploration of aesthetics and functionality. Its disappearance would be the removal of a part of modern architectural cultural memory.” He urged the government to incorporate modernist architecture into long-term cultural policies, establishing a social protection mechanism through tax incentives, maintenance funds, and educational interventions.

Hope for collaborative efforts to save design heritage

While the public attention sparked by the auction has created urgent pressure, it has also generated new opportunities. Several university architecture schools have expressed their willingness to participate in the subsequent restoration project, and some volunteer designers have already submitted preliminary restoration proposals. If funding is successfully secured, this project could become a model case for the reuse of public architectural heritage in the UK in recent years.

Hannah McDonald, director of the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust, stated: “We not only aim to preserve this building but also to breathe new life into it. It could serve as an internship base for young architects or as a convergence point for design exhibitions and community education.” She emphasized that the process of transitioning from “endangered to revitalized” itself embodies cultural vitality.

The future fate of this building is capturing the attention of society

The auction results are expected to be announced in early August. Currently, the Bernat Klein Foundation is raising funds through crowdfunding platforms, charitable foundations, and cultural institutions, aiming to achieve its conservation goals before the deadline. Regardless of the auction’s outcome, the public discussion sparked by this modernist building has refocused attention on the relationship between architecture and culture.

In a society that is constantly evolving and being redefined, the question of which buildings are worth preserving and which spaces should be given new uses has become a crucial issue in urban governance, cultural policy, and public consciousness. And this glass box nestled in the forest may well be the perfect illustration of this very issue.

Leave a comment