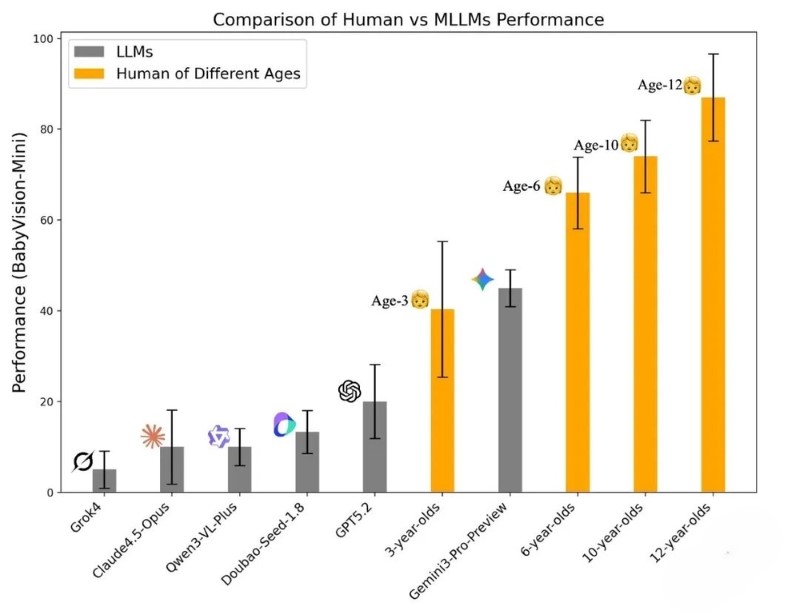

On January 12, 2026, Sequoia China xbench and the UniPatAI team jointly released the multimodal understanding evaluation suite BabyVision, and its test results sent shockwaves through the industry: The core visual capabilities of most current top-tier multimodal large models are significantly lower than those of 3-year-old children, with only one model barely meeting the baseline for 3-year-olds. Even the best-performing model achieved an accuracy rate of less than 50% in the full-scale test, exposing the systemic lack of visual capabilities in large models.

Test Results: Large Models Lag Far Behind Humans in Visual Performance

The BabyVision evaluation suite consists of two versions: Mini and Full, designed to eliminate interference from language reasoning and accurately assess the pure visual capabilities of large models. The initial BabyVision-Mini test includes 20 vision-centric tasks with strict control over language dependence, where answers must be derived entirely from visual information. Meanwhile, control groups of children aged 3, 6, 10, and 12 were set up for comparison.

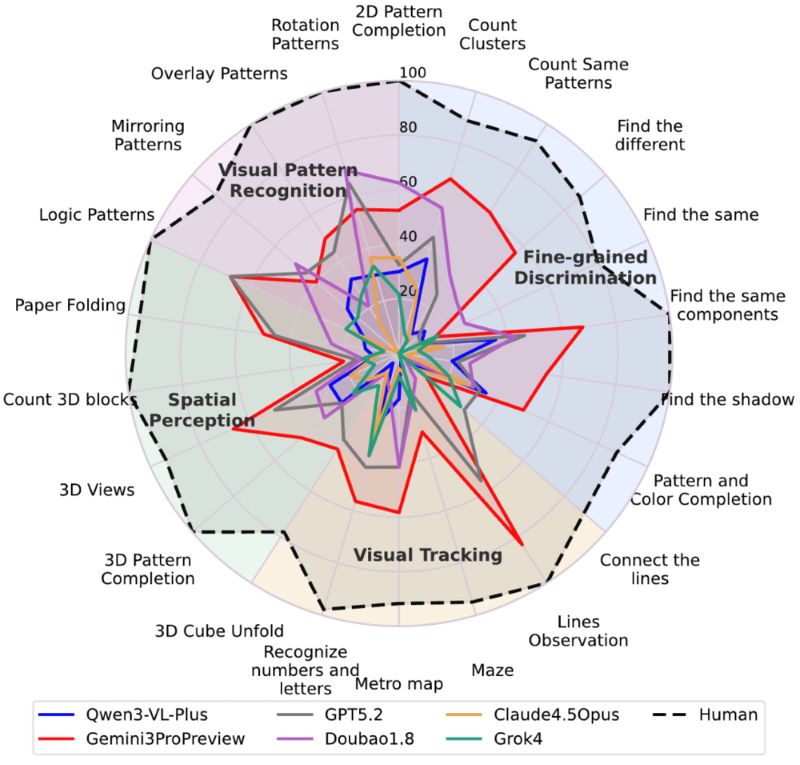

The results showed that most top-tier models scored significantly below the average level of 3-year-old children. The only model with relatively good performance, Gemini3-Pro-Preview, barely exceeded the baseline for 3-year-olds but still lagged behind 6-year-olds by approximately 20 percentage points. A typical example is a “garbage classification” connection question: Children could easily complete the task by following the lines intuitively, while Gemini3-Pro-Preview, despite writing a lengthy “step-by-step tracking” reasoning process, still gave the wrong answer (A-Green, B-Yellow, C-Blue instead of the correct A-Blue, B-Yellow, C-Green). When expanded to the full-scale BabyVision-Full evaluation with 388 questions, 16 human participants with bachelor’s degrees or above achieved an accuracy rate as high as 94.1%. However, the performance of large models was dismal: among closed-source models, the top-performing Gemini3-Pro-Preview had an accuracy rate of only 49.7%; among open-source models, the strongest Qwen3VL-235B-Thinking achieved less than 22.2%, and other open-source models scored between 12% and 19%.

In daily scenarios, the powerful language reasoning and multimodal learning capabilities of large models often mask their visual shortcomings. When dealing with image-related problems, they first convert visual information into textual descriptions and then solve the problems through language reasoning, rather than relying on true visual capabilities. Once stripped of language support, their inadequacies in visual processing are fully exposed.

Four Core Challenges: Comprehensive Lack of Visual Capabilities

Tests indicate that the visual shortcomings of large models are not limited to a single area but represent a comprehensive deficiency in four core categories: fine-grained discrimination, visual tracking, spatial perception, and visual pattern recognition, presenting four typical challenges.

The primary difficulty is the lack of non-verbal details. Humans can intuitively perceive pixel-level differences such as boundary alignment and tiny protrusions through geometric intuition when dealing with tasks like puzzle completion. However, when models describe shapes using linguistic generalizations such as “like a hook with two legs,” subtle visual differences are erased, making the options “almost identical” in the token space.

In visual tracking tasks, humans can lock onto a line and track it continuously, but models need to convert paths into discrete linguistic descriptions like “left/right/up/down.” When encountering intersections, they are prone to path divergence, degenerating from “tracking” to “guessing the endpoint.”

The lack of spatial imagination is equally prominent. In tasks such as 3D block counting and perspective projection, models rely on language reasoning that struggles to reconstruct real spatial structures, often missing hidden blocks or misjudging projection relationships.

In terms of visual pattern induction, humans excel at extracting structural rules from a small number of examples, while models tend to misinterpret “structural rules” as “appearance statistics” such as color and shape, leading to hallucinations when migrating rules.

The research team pointed out that the core crux lies in the “unspeakable” nature of the test questions—visual information cannot be fully verbalized without losing details. When models compress visual information into tokens, a large number of key details are lost, ultimately leading to reasoning errors. However, there is a promising direction for improvement: the team found that enabling “visual reasoning through visual operations” may hold potential. For instance, Sora2 successfully drew part of the connected images, though it can currently only complete single tasks and has not yet formed generalizable capabilities. This insight is part of the latest AI news highlighting emerging solutions to address foundational limitations. The team emphasized, “It is hard to imagine a robot with visual capabilities inferior to children reliably serving the real world.” The future development of multimodal intelligence needs to fundamentally rebuild the visual capabilities of large models, rather than relying on the “roundabout problem-solving” model of language reasoning.