On the latest 10th anniversary of the death of Gabriel García Márquez, a representative figure in Latin American magical realism, his iconic work One Hundred Years of Solitude was adapted into a television series by Netflix. The series has sparked widespread discussions, and literary adaptations have become a new channel for the global dissemination of Latin American literature. Looking at the development of Latin American literature as a whole, it reflects the continent’s trajectory from cultural dependence to independent innovation. It has not only enriched the world literary canon but also opened up new possibilities for literary creation in other regions. Today, Latin American literature continues to maintain a strong social awareness and spirit of cultural exploration, continuing to shine on the world literary stage.

“Loneliness” is the essence of García Márquez

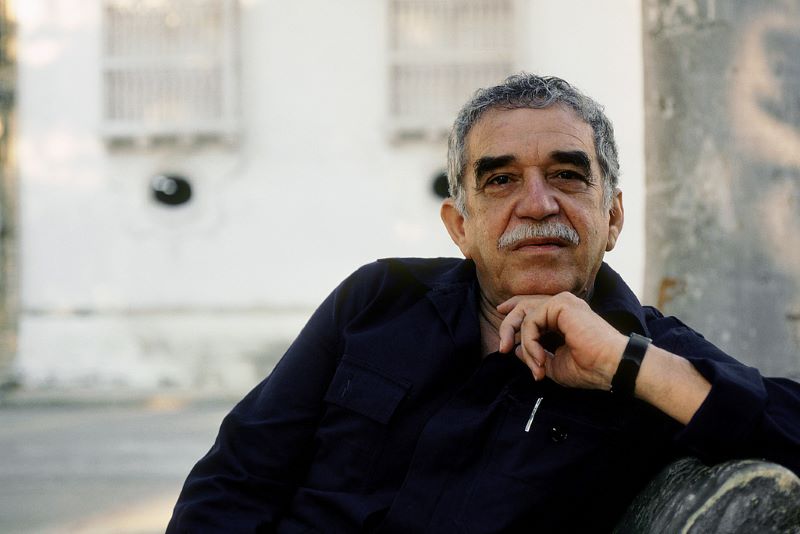

Gabriel García Márquez, born on March 6, 1927, was a Colombian writer and journalist, and one of the most prominent figures in Latin American magical realism. He is considered one of the most influential writers of the 20th century. In 1982, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature for One Hundred Years of Solitude, with other notable works including Chronicle of a Death Foretold and Love in the Time of Cholera. After his death on April 17, 2014, then Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos called him “the greatest Colombian of all time.”

Before his fame, Márquez had a difficult life. As a “small-town left-behind child,” his grandparents had a significant influence on his early development. “Loneliness” is the most prominent theme in Márquez’s works and runs throughout his creative process. He repeatedly pointed out the crux of “loneliness”: using others’ models to explain our life reality only makes us feel more alienated, and increases our sense of loneliness.

The hardships Márquez experienced in his youth gave his work a deeper, more somber hue. “Writing books is a suicidal profession,” Márquez candidly wrote in his first column after finishing One Hundred Years of Solitude. When discussing the complexity and challenges of his work, he explained in interviews that when he completed the novel in 1966, he was several months behind on rent and had started writing screenplays—a project he immersed himself in while living in Mexico.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is undoubtedly Márquez’s most important work. When the book was finally published in Argentina in June 1967 after many setbacks, it became an enormous commercial success, earning praise from critics and propelling Márquez to fame. In 1999, it was ranked third in Le Monde‘s list of the 100 best novels of the 20th century. It also holds the record as the best-selling book originally published in Spanish. Peruvian writer and Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa called One Hundred Years of Solitude “the most important work in our language,” while Chilean poet and Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda referred to it as “the Don Quixote of our time.”

Márquez’s success in literature also brought “Latin American magical realism” to the world. This style blends magical elements with ordinary and realistic contexts. According to Márquez, his grandmother was the “source of my magical, superstitious, and supernatural views of reality.” No matter how strange or unbelievable her stories seemed, she always presented them as irrefutable facts. This deeply influenced his work, where reality is a key theme. His early works, such as No One Writes to the Colonel and The Evil Hour, reflected the reality of life in Colombia, with Márquez excelling in presenting the most horrifying and unusual events in a deadpan manner.

As Gerald Martin, the biographer of García Márquez: A Life, noted, when Márquez finished One Hundred Years of Solitude, he had undergone a transformation: “He wrote down his misfortunes because they were about to end.” Nearly 60 years later, this story has been adapted into a successful TV series. Netflix’s data shows that the series ranks third among the platform’s most-watched non-English-language productions. Colombia’s El Tiempo reported the premiere of One Hundred Years of Solitude with the headline: “Gabo (Márquez’s affectionate nickname) and the yellow butterflies take flight on screen,” calling it “a long and challenging journey, as the platform will bring Márquez’s magical realism, which conquered world literature, to 190 countries.”

In reality, Márquez had firmly rejected the idea of adapting One Hundred Years of Solitude into a film, but his son Rodrigo said, “My father once said that if One Hundred Years of Solitude could be filmed in Spanish in Colombia, he might consider it.” However, these concerns are no longer important. As the premiere of the One Hundred Years of Solitude series became a cultural celebration in Bogotá, the director, Laura Mora, stated in an interview with El Espectador that she aimed to “capture the poetic beauty of the novel in images,” allowing thousands, even millions, of new readers to step into the novel and search for their own “Macondo.”

Rooted in Latin America, connecting reality with the fantastical

Latin American literature has left a vivid mark on world literary history with its unique narrative style and profound cultural content. From pre-Columbian myths and legends to the highly acclaimed magical realism of today, Latin American literature showcases astonishing creativity and vitality.

The origins of Latin American literature can be traced back to the pre-Columbian indigenous literature, such as the Mayan civilization’s Popol Vuh and other mythological texts. During the colonial period, Latin American literature largely followed the aesthetic traditions of Spanish literature, particularly the Baroque style of the 16th century. With the influence of French Enlightenment ideas in the 18th century and the independence movements across Latin American nations, Latin American literature began to develop its own unique narrative characteristics and entered a new stage. Esteban Echeverría introduced French Romanticism to Argentina, injecting new vitality into local literature. In 1845, Argentine educator and future president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento wrote Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, which explored concepts such as “civilization” versus “barbarism,” “city” versus “country,” and “European civilization” versus “Latin America,” reflecting the social landscape of early 19th-century Argentina and envisioning a modern future. This work became a landmark in Latin American literary history.

In the 20th century, Latin American literature presented a richer diversity. Venezuelan politician and writer Rómulo Gallegos’s Doña Bárbara reflected the socio-economic reforms in Venezuela in the 1920s, depicting the struggle between civilization and barbarism, progressive forces and conservative forces, and expanding the influence of Latin American literature.

Furthermore, during the 1920s to 1940s, the avant-garde movement spread from Mexico to Argentina. The avant-garde literary works of this period were primarily reflected in poetry and novels, focusing on urban life and utilizing techniques such as inner monologues, dreams, and stream of consciousness, addressing the fate of Latin American nations and peoples. A new wave of avant-garde poets emerged, such as Peruvian César Vallejo, Chilean Vicente Huidobro, and Pablo Neruda. In the mid-20th century, Latin American literature entered its true golden age. Alejo Carpentier integrated surrealism with local elements, founding “fantastic realism,” which laid the groundwork for magical realism. Works by Peruvian author José María Arguedas and Mexican writer Juan Rulfo, particularly Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, showcased the charm of local cultures through the lenses of Peru and Mexico.

After World War II, particularly following the Cuban Revolution, Latin American people underwent further awakening. A large number of literary works emerged, focusing on social darkness, anti-imperialism, opposition to military dictatorship, and critiques of oligarchy. The “Latin American Literary Boom” of the 1960s brought the region’s literature to the center of the global stage. Colombian author Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude became the flagship work of magical realism, and with Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa’s Nobel Prize, Latin American literature cemented its position on the world literary map. Together with Mexican author Carlos Fuentes and Argentine writer Julio Cortázar, they were known as the “Four Pillars of the Latin American Literary Boom.”

The golden age of the “Latin American Literary Boom” was primarily dominated by long novels and short stories. Through linguistic innovation, nonlinear narrative, and the use of fantastical elements, these works redefined traditional realism. They reflected national and regional identities, social upheavals, and the conflicts between individuals and society, seamlessly blending the real with the fantastical through magical realism, presenting rich narrative layers. With the support of publishing in the U.S. and Europe, these works spread globally, becoming a defining phenomenon in world literature and profoundly influencing literary creation outside of Latin America.

The post-boom era marks a transitional phase following the literary boom. It is characterized by a closer connection to popular culture, an emphasis on social critique, and a more diversified style. Post-boom literature focuses more on narrative realism and readability, expanding its audience and making literature a more direct tool for social criticism.

“Injecting new moral power into Latin American literature”

Masters like Márquez, Vargas Llosa, and Cortázar, with their extraordinary talent, have shaped the glorious image of Latin American literature on the international stage. However, 21st-century Latin American literature is entering unknown realms as innovators, facing multiple challenges of contemporary society, exploring new themes, and adopting diverse styles, demonstrating a global vision and endless possibilities that transcend regional boundaries.

Latin American literature has always been regarded as a mirror of social reality, and a particularly notable feature of contemporary Latin American literature is that it is no longer confined to traditional narrative frameworks. Instead, it responds to the calls of the times through diversified themes. Compared to the collective, symbolic narrative approaches of the “Latin American Boom,” today’s Latin American literature tends to start from individual experiences and local perspectives. As Argentine literary critic Ezequiel Alemian said: “Latin American writers no longer bear the burden of representing the entire continent. Their stories, though rooted in local settings, address universal global issues.” For example, the issue of migration has become one of the core themes in contemporary Latin American literature. Mexican author Valeria Luiselli’s The Lost Children Archive deeply examines the immigration crisis at the US-Mexico border. The book, through documenting the real conditions of child migrants, condemns the violence and indifference within immigration policies and reveals the profound global power structures behind cross-border migration. This narrative approach, which reflects universal issues through individual stories, injects new moral strength into Latin American literature.

At the same time, environmental issues are also an important theme in contemporary Latin American literature. Bolivian author Liliana Colanzi, in Our Share of Night, uses indigenous worldviews and science fiction elements as a starting point to explore the cultural and ecological consequences of resource exploitation.

Magical realism is the hallmark style of Latin American literature. In the 21st century, this classic narrative form has been endowed with new meaning and has become an innovative tool for exploring contemporary issues. Argentine author Mariana Enriquez combines magical realism with horror literature in her novel Things We Lost in the Fire, using magical techniques to examine the political trauma during Argentina’s military dictatorship. This combination not only reshapes the narrative boundaries of magical realism but also demonstrates its flexibility in revealing historical scars and social shadows.

In addition, literary adaptations have become a new channel for the dissemination of Latin American literature. In addition to Netflix’s adaptation of Márquez’s classic work One Hundred Years of Solitude, Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate has also been adapted into a film, opening a window for audiences around the world to understand Latin American culture. These adaptations not only expand the influence of Latin American literature but also organically combine Latin American narrative traditions with modern media tools. However, as Cruz Castillo from the National Hispanic Media Coalition points out, these works break the traditional stereotypes of Latin American literature, but there is also a need to be cautious of oversimplification and commercialization of their cultural core.

21st-century Latin American literature presents its unique charm through its diverse and complex forms. From the exploration of social issues to the new interpretations of magical realism, and its powerful influence in the international literary landscape, Latin American literature is not only a reflection of regional culture but also a distinctive mode of expression in the context of globalization. As Chilean literary critic Lina Meruane stated: “Latin American literature is no longer a fixed form, but an ever-expanding space where individual voices together build a collective literary horizon.” The power of Latin American literature lies in its ability to connect universal values through concrete experiences, offering global readers a reading experience that is both close to reality and full of imagination.

Leave a comment